Summary

That article briefly develops the evolution of Byzantine clothing as a distinct case of clothing during the medieval period as a result of the continuous interaction between the West and the East. This development is traced through the analysis of the garments, fabrics, colors, and styles that dominated the Byzantine state. The timeframe spans from the 4th century to the 15th century, with special emphasis on the first fall of Constantinople in 1204. Additionally, the article examines issues related to the use of Byzantine clothing and their aesthetic impact on the social hierarchy within Byzantine society as well as in the broader societies of the West and the East.

Part 1: The evolution of clothing in the Byzantine Empire

The development of Byzantine dress as a distinct case of clothing during the medieval period was mainly a result of the constant interaction between the West and the East. The information we get about Byzantine clothing comes from mosaics, images, and literary sources, but which rarely show any correlation between description and artistic impression of the clothes1 .

In an fantastic timetable we can place some points-areas in the clothing and its evolution, over the centuries, of the existence of the Byzantine Empire. Intentionally our plan will stop at 1204, as from then on Byzantine clothing begins to become more and more similar to Western clothing, at least as far as imperial and aristocratic clothing is concerned.

With that being said, we can place the first point in the 4th century. Lilie-Ralph author of "Introduction to Byzantine History"2 states that during the 4th century the clothing of the Byzantine Empire was the same as that of the Greco-Roman period. After the fall of the Roman Empire and the creation of the Byzantine Empire by Constantine in the 4th century, it did not necessarily mean that the population and its cultural habits changed overnight. There was no serious difference between Byzantine society and Roman society. Ancient Greek and later Roman clothing continued to be the main garment for men and women during the early Byzantine period. Clothing at that time was primarily intended to protect people from temperature changes3. That is the tunic dominated as the most basic garment of daily life.

After two centuries, in the 6th, we have the introduction of silk-making into the Byzantine empire, due to the adoption of the Chinese empire's secret of silk, the silkworm. Silk garments began to circulate among the circles of the rich and Byzantium, in this way, further developed its commercial activity. So Runciman mentions that looms "where the most expensive fabrics were woven" were placed in the gynaeconites of the Great Palace, as the production of silk was an imperial monopoly4. This "secret" production of silk gradually reduced imports of silk from the East and saved considerable money for the Byzantine state.

During the middle Byzantine period (7th and 8th centuries) Greek and Roman cultural elements were replaced with more medieval, Christian and Eastern influences creating a new type of clothing, more in line with Christian ideals5. The clothing habit of the Byzantines changed during the middle and late Byzantine period, as there was a modification of the clothes by incorporating eastern elements and reducing the Roman ones. In fact, in the Middle Ages, as Parani mentions, the clothes were created from smaller fabrics, sewn between them, this is found later, as it is a western influence6.

From the 9th century, Parani informs that the chlamydia was the distinguishing element in official attire, namely the mantle, and V-neck garments. While in the middle of the 11th century women's clothing changes, and dresses are added that cover the neck, with narrow but wide wrist sleeves. In the 12th century, the preeminent male garment, the kaftan, appears, a kind of cloak or shirt, with a buttoned opening at the front. Finally, from 1204 onwards, as mentioned, Byzantine clothing begins to be increasingly influenced.

Men's and women's clothing, headdress and footwear in Byzantium

The men's wardrobe in everyday clothing consisted of the "cloak" (dalmatica), a shirt with wide sleeves7. It was worn with a belt and as a rule did not exceed the length of the knee, and the sleeves of the arms were long. Above the tunic, the mantle or chlamyda is placed, which was worn in two ways: either tied on the right shoulder with a pin or with an opening for the head. From the 9th century V-neck garments began to become more popular, as did the Byzantine habit of wearing an outer tunic, which reached to the calf with a hole in the front8. Other types of men's clothing found in the Byzantine Empire included a short coat with long narrow sleeves and a skirt, worn with a pair of trousers9. In general, the Byzantines until the middle Byzantine period preferred the simplest clothes, this "habit" changes and the clothes are presented more elaborately and more luxuriously.

On the other hand, women's clothing included basic dresses, cloaks, jewelry and the headdress. The dresses, called stola, were ankle-length, high-necked, turtleneck-style, and had long, narrow sleeves, which were worn with or without a belt. Women's cloaks were not wrapped around the body, but fastened at the front with a pin. In various regions of mainland Greece, there was a further addition to women's clothing, the 'anapetarin' or 'anapetarikin', which was a cloth with fur details placed over the shoulders without the sleeves passing through. Other variations were either knitted fabrics, of various shapes, which were called "boksadaki" or "shawl". After 1204 the dresses became more western, i.e. they stopped being so closed towards the neck and had simplistic decoration.

The decoration of the head and face was an advantage of the richest social strata of the Byzantine Empire. In fact, during the Palaiologos dynasty, it had become widespread towards the upper classes. The men had the so-called "Caesar Haircut", an influence from the Roman empire's past. Women preferred braids decorated with pins or ribbons and other jewelry to decorate the head. The use of hats or crowns was also a privilege of the upper classes and mainly of the Christian clergy. A paradox is that in the 7th century the shaved face was considered vulgar and a habit brought from the west, while from the 13th century onwards it was adopted by the upper classes.

Footwear in the first centuries did not differ from Roman sandals or covered shoes. They were of less special importance as both in the philological sources and in the Byzantine art, from where we get the information about the rest of the clothing habit of the Byzantines, very few references are made. For example the image below depicts two pairs of shoes, one a child's and one probably a woman's, from the 5th century.

Byzantine Differences in Clothing and their meanings

Byzantine society was quite hierarchical, so clothing was another differentiating element between hierarchical positions, whether it was political, religious, economic or social, where silk fabrics and those of good quality were reserved for the "excellent" and the imperial court , while linen and other fabrics of lower quality were intended for the poor Byzantines. There was a strong Christian element in the dress of both rich and poor. More specifically, the "scaramaion", as it appears in the literary sources and mainly, according to Koukoules10, by Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, was a garment, which was intended for the nobles, mainly for official occasions and was kept in the Great Palace.

In addition, color was a major element in differentiating the offices, as the different colors, designs and embroideries indicated the different offices. The chlamyda, for example, was an insignia for all Byzantine positions, especially the imperial one, where they appeared in purple, or otherwise "sea", and with golden details, and even the empress had the right to wear one. Instead the officials wore a white chlamyda with a pair of purple tablias. Of course, after 1204, the chlamys ceases to be a sign of the court hierarchy and the headdress appears in the foreground, which, depending on the type, determined the person's position in the court. Finally, the other parts of the emperor's uniform, as well as the officers whose uniforms were particularly impressive and well-kept, had dark colors so that the blood would not show in case of injury.

Finally, clothing could be given as an asset in payment of wages or debts and was sometimes offered as security in financial transactions, due to the monetary and sentimental value they acquired, and was therefore considered a sought-after gift among the Byzantines, as well as its diplomatic enterprises. Byzantium. In fact, the ceremonial awarding of clothes by the emperor to the officials, in addition to the direct display of wealth and power, contributed to the consolidation of bonds of loyalty and solidarity between him and the court. Its use as a decorative element in the imperial palace and in the streets of the cities during important ceremonies highlighted the special Byzantine clothing that Byzantium had shaped for the visitors of the empire.

Part 2: Aesthetic influences of Byzantine clothing (Eastern aesthetics and Western aesthetics)

In the second part of the article, a few words are mentioned about the eastern medieval aesthetics and then about the western one. This position is purely chronological, because during the first centuries Byzantium was quite influenced by Arab and Persian elements. So, when we refer to the "eastern medieval aesthetics" we are talking mainly about the regions which Byzantium bordered to the east and had Arabic, Persian, from the 7th century onwards, Muslim elements, while chronologically we are placed towards the end of late antiquity, in the early Byzantine years. The main characteristics are the religious influence through the clothes, the luxury and the glitter, the elaborate decoration and finally, as is natural, the combination of cultures.

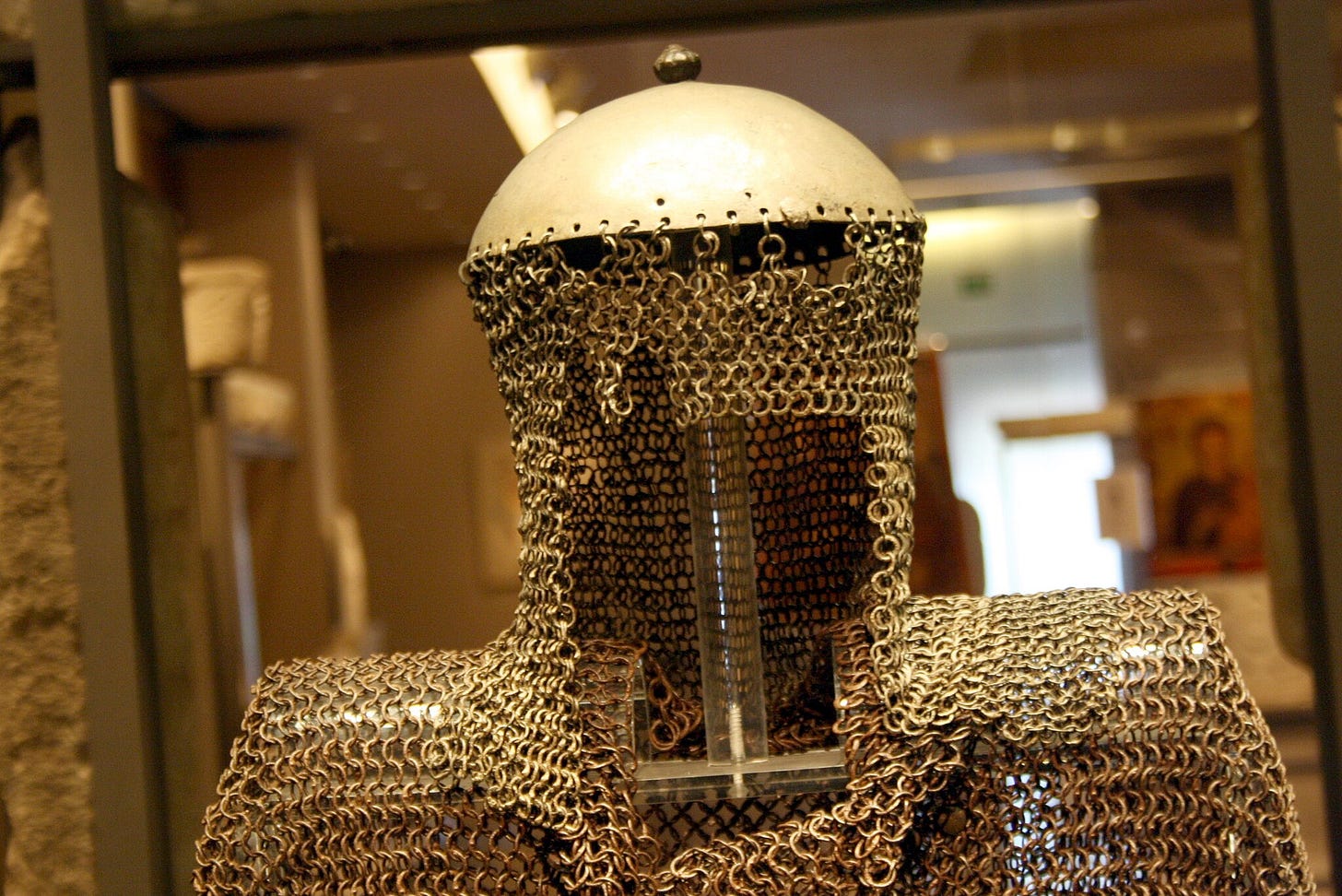

On the other hand, moving to Western aesthetics, which is later, we refer to the post-1204 period as after the first fall of Constantinople and the establishment of the Frankish states, Byzantine culture was more directly influenced by Western mentality and culture. Characteristics we find are: Western-style dresses for the women of the ruling class, there are changes in the soldiers' armor and often replacing it with western armor, new fabrics and new styles are used, western jewelry is used, and crowns and western hats are used.

But beyond the influence of Byzantium from the West and the East, the influence and spread of Byzantine fashion in Western Europe through trade and cultural exchanges that lasted until the fall of Constantinople was also important. At the same time, the influence of Byzantine fashion in Asia Minor began to decline after the appearance of the Turkic races and the rule of the Ottoman Turks.

In the West, therefore, Byzantine styles and technical clothing influenced the clothing choices of mainly aristocrats, who wished to beautify the aesthetics of the Byzantine Empire even after its fall in 1453. Finally, Byzantine embroidery techniques were also adopted in the West, adding intricate details and designs to clothing11.

Epilogue - Conclusions

In conclusion, we can say that Byzantine clothing was a mixture of Western and Eastern influences, as we saw before. The influence of Roman customs that already existed from the early years of the Byzantine Empire, were enriched with eastern cultural elements and then with western ones, creating a special diverse culture, as well as a separator between the hierarchical classes of Byzantine society.

In addition, it is observed that the clothes were separated according to gender, age and family status. There was diversity and accordingly the professional orientation, the racial and the religious.

The fabrics, even those as distinguished from the study of the literature, vary, both in names and in types. Particular emphasis is placed on the names of the colors, especially on the export of purple, which, as mentioned above, was also called "sea". In fact, there are many examples where the names of fabrics and colors are identical. Of course, this identification, as I could see from the literature, made the work of researchers on this topic difficult.

Finally, the opinion is correctly formulated that the Byzantines attached particular importance to their clothing, as well as retained until 1204 the hierarchical mentality that pre-existed in the Roman Empire. The characteristic chlamys, which appears in several mosaics, most notably the mosaic found in the church of St. Vital, in Ravenna, Italy, exemplified this Roman continuity.

Bibliography

Ball, J., 2006. Byzantine Dress: Representations of Secular Dress (The New Middle Ages). s.l.: Palgrave Macmillan Publications.

Emmanuel , M., 1994. Headdresses and headdresses of empresses, princesses and ladies of the aristocracy in Byzantium. Bulletin of the Christian Archaeological Society, 11 January, Issue 17, pp. 113-120.

Ettinghausen, R., Grabar, O. & Jenkins, M., 2003. Islamic Art and Architecture 650-1250. 2nd Edition edited by s.l.: Yale University Press.

Lilie, R. -. J., 2011. Introduction to Byzantine History. Athens: HERODOTOS Publications.

Mythesius, A., 2016. Cloth, colour, symbolism and its meaning in Byzantium (4th - 15th centuries). Bulletin of the Christian Archaeological Society, Issue 36, pp. 345-362.

Parani, M., 2008. Fabrics and Clothing. In: The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pendergast, S., Pendergast, T. & Hermsen, S., 2003. Fashion, Costume, and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear Through the Ages. California: UXL Publications.

Prani, M. G., 2007. Cultural Identity and Dress: The Case of Late Byzantine Court Costume. Jahrbuch Der Österreichischen Byzantinistik, Issue 57, pp. 95-134.

Rooijakkers, C., 2017. New Styles, New Fashions: Dress in Early Byzantine and Islamic Egypt (5th-8th centuries). In: Late Antique History and Religion: New Themes, New Styles in the Eastern Mediterranean: Christian, Jewish and Islamic Encounters, 5th-8th Centuries. s.l.: Peeters Publishers, pp. 173 - 203.

Runciman, S., 2016. Byzantine Civilization. Athens: Metaichmio Publications.

Varmazi, V. N.-., 2013. Byzantine Civilization: 4th - 15th centuries. Thessaloniki: Kyriakidis Brothers Publications S.A. .

Ioannidis, G., 2013. The Clothing of the Byzantines through the surviving texts, Athens : s.n.

Koukoules, F., 1995. Byzantine Life and Culture. Athens: PAPAZISI Publications.

Koukoules, F. (1995). Byzantine Life and Culture (Vol. 6). Athens: PAPAZISI Publications, p. 267.

Lilie, R.-J. (2011). Introduction to Byzantine History. (X. D. Tsatsoulis, Editor, & X. D. Tsatsoulis, Trans.) Athens: IRODOTOS Publications., p. 164.

Parani M, (2008) Fabrics and Clothing. In R. Cormack, J. Haldon, & E. Jeffreys, the Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 407

Runciman, S. (2016). The Byzantine Civilization. (A. Pappas, Trans.) Athens: METEICHMIO Publications, p. 231.

Lillie, R. -J., as above, p.167.

Parani M, as above, p. 411.

Sara Pendergast et al., Fashion, Costume and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations and Footwear Through the Ages (2), California: Publications UXL, p. 261

Parani M, as ab., p. 411

In the same, p. 412.

Koukoules F., as ab., p. 270

This part is based on things I read and is more like my theories about the influence of Byzantine Civilization. I also recommend some excellent works in bibliography at the end of the article.